The Obstacles to Justice, Between Impunity and Fear

The fall of the regime marked a historic rupture, but the implementation of genuine transitional justice encounters obstacles that go far beyond institutional questions, memory trauma, community fractures, and sometimes irreconcilable expectations within a society devastated by thirteen years of war. Despite the collapse of central power, key elements of the security apparatus persist. Former intelligence officials and militia members still control certain areas, particularly in rural Latakia or Sweida, where recent massacres have reminded everyone that entrenched brutality continues to survive [35].

For decades, the Syrian intelligence services mukhabarat [36] were the backbone of Assad’s power, exerting their pervasive influence through constant surveillance, systematic torture, and enforced disappearances. According to Iyad Al Shaarani, as long as these oppressive structures are not dismantled and their leaders brought to justice, Syrians cannot be given any guarantee about their future safety. Michel Ghaith lives this injustice daily. His father, a former prisoner tortured and executed by the regime, haunts his memory while the men responsible for his death walk freely in his neighborhood. “Every day, I see the murderers of my father. The accomplices of the former regime stroll around with complete impunity. The new government must take real measures. Some people think a form of justice has begun. But for all those who suffered all these years, can they really accept this impunity ?” This unresolved legacy places a heavy burden on attempts to establish justice. Victims are afraid to testify, knowing that their tormentors still circulate freely among them. Iyad Al Shaarani summarizes this painful deadlock, “We cannot ask victims to testify freely as long as the perpetrators still walk around in uniform in their neighborhoods.”

The case of Mohammed Hamsho, according to a Reuters investigation published on 24 July 2025 [37], illustrates this persistent impunity. This businessman is accused of having used his metallurgy factory to process metals taken from destroyed residential areas, acting as a front for Maher al Assad, the president’s brother. The latter commanded the Fourth Division of the Syrian army, linked by Western governments to the production and trafficking of Captagon. Returning to Syria in January 2025, Hamsho now lives under state protection in a luxurious penthouse in the wealthy Malki district of Damascus.

The conflict has left behind a deeply divided Syria. The regime systematically instrumentalized communities, Sunnis, Alawites, Kurds, Druze, and Christians, turning them against one another to prevent national solidarity. This strategy of fragmentation has left deep scars in the Syrian social fabric. As activist Wafa Mustafa [38], whose father disappeared in the regime’s prisons, emphasizes, “Syria will not be able to rebuild as long as we do not have the truth” The Guardian, 2 October 2025. The challenge lies in constructing a national narrative capable of recognizing the suffering of all communities without fueling new divisions. A very real danger looms, that of an imposed amnesia in the name of stability. Certain leaders call for “forgiveness” and forgetting in order to turn the page. But the victims reject this logic firmly. Iyad Al Shaarani speaks plainly, “There is no lasting peace without truth. Any compromise that erases the memory of the victims prepares the next civil war.”

The legitimacy of the current judicial system is gravely compromised. Many magistrates who collaborated with the regime still occupy their positions. Iyad Al Shaarani is unequivocal, “Compromised actors cannot be the architects of a transition toward justice, because they embody precisely the abuses that justice claims to correct.” Robert Petit, head of the United Nations International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism IIIM [39] for Syria in Geneva, confirms this, “Transitional justice cannot be credible if it relies on institutions that were complicit in crimes. It must be built on new actors, trained, protected, and legitimate.” Syrian lawyer Noura Ghazi, founder of NoPhotoZone [40], denounces the complete absence of a legal framework, “There is no law criminalizing war crimes or crimes against humanity in Syria, no specialized court, no competent judge. The entire process is distorted. For accountability to exist, there must be an authority ready and qualified to implement it, and that is not the case. Nothing happening today meets international standards of transitional justice.” She also describes revolting institutional corruption, “Some literally sell detainee files to families. Money is demanded in exchange for information, or even false death certificates. It has become a market of human suffering. These practices always existed, but today it is worse, because impunity is total. Families pay hoping for truth about their loved ones, but most of the time they receive false documents. There is no trust left in the institutions.” Beyond corruption, she condemns widespread inaction, “Today in Syria, we have no elected authority, no normal situation. We hear speeches, but no concrete action. Victims have immense needs at every level, and nothing is being done to respond.”

International examples show that concrete reforms are essential to guarantee non repetition of abuses. In Argentina, the dissolution of repressive bodies and the creation of new security forces respectful of human rights marked major progress. In South Africa, police reform and the establishment of independent civilian institutions limited abuses. By contrast, the lack of deep transformation of police forces in Bosnia maintained divisions and fueled lasting mistrust.

From Far Falasteen to Al Khatib and through the infamous Saydnaya prison, colossal quantities of documents were burned by the forces of the former regime just before its fall in order to cover up their crimes. HTS fighters were deployed in the different branches to protect the remaining documents so that families and relatives could consult them later. Photo 1, Far Falasteen, Branch 235 of the intelligence services guarded by rebel fighters, 17 December. Photo 2, Al Khatib, Branch 251, a detention and torture center of the General Directorate of Intelligence, where relatives consult the remaining documents in the hope of finding traces of a missing loved one, 11 December 2024. Damascus, Damascus, Syria. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

On the forensic level [41], the discovery of mass graves in the provinces of Damascus and Homs [42], among others, illustrates the scale of the crimes committed. Each exhumation reopens the pain of families and presents major technical challenges for identifying the disappeared. An expert on former Yugoslav investigations compares these mass graves to those of that region while emphasizing that in the absence of a solid judicial apparatus, “each body recovered risks becoming an anonymous statistic rather than evidence.”

DNA research is often impossible due to a lack of resources, specialists, and comparative databases, some elements have been corrupted or destroyed, and entire families have been wiped out. This situation creates a double injustice, the victims were murdered and their identification is almost impossible, depriving their relatives of a dignified mourning process. Despite these obstacles, Noura Ghazi insists on the urgency of acting, “Even if one day a mechanism of accountability were established, it would take time. But in the meantime, we must not forget the immediate needs of victims.” Her words remind us that transitional justice is not only a matter of courts and trials but also of an immediate human response to the suffering of survivors.

The discoveries of mass graves in al Tadamon have deeply affected Syrians as well as the international community. These collective burial sites, revealed through an investigation combining academic research, testimony from former military defectors, and the work of Syrian NGOs, shed light on the scale of extrajudicial executions orchestrated by security forces.

A video published in 2022 by researchers Annsar Shahhoud and Uğur Ümit Üngör confirmed the existence of these methodical massacres, “civilians, their hands tied, are executed and then thrown into a pit by members of militias loyal to the regime.” The investigation made it possible to identify one of the direct perpetrators captured in the video, Amjad Youssef, a military intelligence officer now sought by several international jurisdictions [43].

The al Tadamon case illustrates a phenomenon far from isolated. Since 2011, other mass graves have been documented in several Syrian regions, including Raqqa, Aleppo, Deir ez Zor, Homs, and more recently in rural areas of Latakia and Sweida. These sites are often detected in the immediate vicinity of military bases or detention centers, according to observations made by local teams composed primarily of volunteers.

For Iyad Al Shaarani, these discoveries carry essential value for any future judicial process, “Mass graves are not only material evidence of crimes against humanity. They are also places of memory for families. Exhumations must be carried out under international supervision with forensic experts, otherwise they will lose all credibility.”

On 18 August 2025, Mohammed Reda Jalkhi, president of the Syrian National Commission for the Disappeared created in May 2025, declared, “We have a map listing more than 63 mass graves identified in Syria.” According to him, work was underway to create a database of missing persons. However, al Tadamon, the tragic macabre stage of the former regime’s bloodstained policy, is an open air cemetery. Every day, residents discover hundreds of bones in the rubble. Lacking resources, they try as best they can to preserve them to prevent stray dogs from scattering them or children from coming across them. Al Tadamon, Damascus, Syria. Photo 1 to 2, 26 September 2025. Photo 3, 25 May 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

The comparison with other international situations highlights major approaches in addressing past atrocities. In Bosnia, for example, the efforts made to identify the victims of the Srebrenica genocide [44] relied on the methodical use of DNA analysis and extensive investigations. This meticulous approach made it possible to give a name to each body recovered, even when this required years, sometimes decades. Similarly, in Argentina, teams of forensic specialists played a central role in recognizing and documenting the crimes committed during the dictatorship. This painstaking work allowed the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo to retrace the fate of their disappeared children, enabling them to hold dignified funerals and begin their path toward mourning.

These examples demonstrate that the search for truth is often long and complex, but that it is an essential step for building collective memory and establishing the foundations of lasting justice. A United Nations expert in forensic anthropology, interviewed in Geneva, emphasized a crucial point. According to him, the exhumation of Syrian mass graves constitutes a decisive moment. If this operation is conducted with care, scientific rigor, and complete transparency, it could become a cornerstone for launching a genuine transitional justice process. Conversely, if these efforts are carried out hastily or exploited for political purposes, there is a high risk of deepening divisions and feeding an already deeply rooted climate of mistrust.

After Franco’s dictatorship 1939 to 1975, Spain long chose national reconciliation through silence, a general amnesty, no prosecutions, and thousands of families left without truth about the fate of their executed relatives buried in anonymous graves. For decades, these graves remained hidden, blind spots of the Transition, symbols of a “pact of forgetting” presented as the price of democracy. But in the early 2000s, something shifted, families, historians, and associations launched a powerful movement, the forensic turn, which restored, literally, a body to the memory of Francoism. Teams of archaeologists and anthropologists began opening graves, identifying victims, returning remains, and finally providing burials and names. This slow and profoundly moving forensic work shook the comfortable narrative of reconciliation without truth, showing that peace does not erase injustice and that no democracy can be built sustainably on forgotten bodies. Spain had to relearn how to face its past, not to reopen wounds, but so that justice and memory could finally become solid foundations of the present.

Transitional justice goes beyond the formal framework of institutions, it resonates deeply in the hopes and aspirations of survivors. Iyad Al Shaarani summarizes this tension with a striking metaphor, “The pain of victims is a volcano beneath the surface. If we do not open a space for truth and justice, this volcano will erupt one day.” During a meeting in Yarmouk [45], a representative of Syrian families of disappeared persons concluded her speech with words filled with determination, these families do not need superficial compassion or empty promises, but an inalienable truth that serves as the foundation for any path toward genuine justice. She reminded everyone that truth is always the first step on this demanding road toward reconciliation and reparation, “We do not need pity, we need truth. And truth is the first step toward justice.”

For his part, Jad al Hamada, nephew of activist Mazen al Hamada [46] and founder of the Tents of Truth [47] in Jaramana, explains, “We need to know what happened. We need compensation, material or immaterial. Compensation does not mean giving us a basket of fruit, but preserving memory, telling what happened, giving schools or public squares the names of the disappeared. I think people are beginning to understand that we need to address responsibilities.” Transitional justice will truly progress when all Syrians fully commit to it. Initiatives such as the Tents of Truth play a crucial role in spreading this idea across different communities.

In post Assad Syria, the Tents of Truth allow the families of victims to express themselves about truth and justice. Here in Yarmouk, commonly called Little Palestine, several families have gathered to speak about this essential pursuit of truth and justice. Thanks to the Tents of Truth, it becomes possible for all Syrians to understand the convictions of the victims’ families. The local organization Casa Palestina, founded by Dr Khaldoun al Mallah photo 4, joins all family gatherings to support them. Yarmouk, Damascus, Syria, 30 May 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

The Nuremberg trial remains a cornerstone of international justice. For the first time, leaders of a regime were tried not only as political authorities but as criminals against humanity. The introduction of charges of crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity paved the way for a universal conception of the criminal responsibility of leaders. According to a former Nuremberg judge quoted by the United Nations, “This trial was not only that of the Nazis, but of the idea that heads of state can kill with impunity.” This legal innovation, although influenced by the power dynamics of the time, remains a fundamental precedent for contexts such as Syria. A credible transition in this country cannot be envisaged without the prosecution of those responsible, whether they stand at the top of the state or acted as direct perpetrators.

However, the experience of the ICTR revealed its limits, only 62 criminals were tried. As Alison Des Forges, historian affiliated with Human Rights Watch [48], noted, the Rwandan case shows that a justice imposed unilaterally is not enough, “Rwanda teaches us that a justice imposed from above is not enough. It must be accompanied by local mechanisms in which society recognizes itself.” This suggests the need for a balance between an internationalized jurisdiction and community based mechanisms capable of responding to the expectations of millions of victims dispersed throughout the country. In the former Yugoslavia, the trials also had a global impact, establishing the responsibility of military and political leaders. However, their slowness and distance often caused frustration and disillusionment in the Balkans. As Mirsad Tokača, director of the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo, emphasized, “The ICTY judgments are essential for History, but they have not healed the wounds of local communities.” Syria could draw a crucial lesson from this experience, although international justice is essential, it must be accompanied by approaches that foster lasting national reconciliation.

The example of Argentina illustrates another significant model, after the end of the military dictatorship 1976 to 1983, the country established the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons CONADEP [49]. Its famous report entitled Nunca Más documented more than 13,000 cases of enforced disappearance, opening the way to historic trials. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, women who gather every week in Buenos Aires holding photos of their disappeared children, have become a universal symbol of the struggle for memory and justice. Their journey echoes Syrian initiatives such as the Tents of Truth or the collectives of families of the disappeared. As Nora Cortiñas, a prominent figure of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, expresses, “We are not seeking revenge, but truth. And truth is the only justice that lasts.”

The experiences of Rwanda, Bosnia, and Argentina offer valuable insights for envisioning the future of justice in Syria. The Nuremberg trials demonstrated the importance of establishing responsibility at the highest levels of leadership. The example of Rwanda highlights the complementarity between international tribunals and community mechanisms. Bosnia illustrates the need to avoid a judicial approach too distant from victims, while Argentina underscores the fundamental role of memory and the families of the disappeared in the process of reconciliation. Iyad Al Shaarani reminds us, “If Syria reproduces the Lebanese model of general amnesty, it will sign the repetition of its wars. If it follows the path of Rwanda or Argentina, it can hope to break with its bloody past.”

A new stage has begun. The work of the IIIM and the arrest warrants issued by European jurisdictions against senior Syrian officials, including Bashar al Assad, have strengthened the conviction that no crime should remain unpunished. From the Caesar archives to the discovered mass graves, these milestones have enabled worldwide recognition of the atrocities committed. But behind this evidence lie the heartbreaking stories of survivors and families. In a testimony collected by Human Rights Watch, a former Saydnaya detainee confides, “Every night, the guards came to take prisoners. We never saw them again. I survived, but a part of me remained locked in that prison.” [50] In Sweida, a mother interviewed by Amnesty International says, “I do not know whether my son is alive or dead. They tell me nothing. How can a mother live like this ?” [51] A survivor of Tadmor prison testifies to the Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre [52], “They had reduced us to numbers. They wanted to erase who we were.” [53]

Um Mahmoud, mother of the first martyr of the revolution in Daraa, carries an unbroken pain. Mahmoud was neither involved in the war nor in the revolution, he was watching the demonstration, his hands in his pockets. Then he was shot, in the heart, “just like that.” On 18 March 2011, her son became the first martyr of a tragedy that tore away thousands of lives and left behind a void that will never close. “I want justice for him, for all those whom Bashar killed, so that everyone knows,” she says, her voice mixing anger and exhaustion, but also a determination that refuses oblivion.

Um Mahmoud, mother of the first martyr of the revolution in Daraa, the cradle of the Syrian uprising. She speaks of her need for justice, not only for her son Mahmoud Al Jawabreh, killed by the army of the former regime during a peaceful demonstration, but also for herself, for her entire country, and for all grieving families. “I no longer sleep because I cannot forget. When justice is done, Inchallah, I will finally be able to begin to know peace.” Daraa, Daraa, Syria, 28 April 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

Today, Syria faces immense challenges in rebuilding its social, political, and judicial fabric. Calls to reform the judicial system resonate through testimonies and reports. In a report published in 2025, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [54] notes that under the former Syrian regime, “judges did not have the independence necessary to oppose the demands of the security services,” and that “magistrates were subjected to constant pressure, making it impossible to guarantee a fair trial.” In essence, several former magistrates describe this reality in similar terms, explaining that they validated convictions they knew were unjust, not out of conviction but out of fear, convinced that refusing to obey meant risking their own disappearance.

After the fall of the regime, many expected to see an entire segment of the Syrian judicial apparatus dismantled. But in the courts, behind desks and piles of dusty files, it is often the same judges who continue to serve today. This is not because they were cleared of responsibility. It is mainly because they spent decades in a system where independence did not exist, and magistrates were part of an apparatus instrumentalized by the regime to validate political trials, forced convictions, or decisions inspired by the security services, sometimes under direct threat. Some now admit it, they signed rulings they knew were unjust, but refusing meant putting their own lives in danger. In a Syria under reconstruction, they could not simply be removed.

The country lacks trained magistrates, lacks jurists capable of taking over, and a total collapse of the justice system would have left a dangerous void. Thus these judges remained, not as symbols of a bygone past, but as indispensable cogs in a system that must be kept functioning while reconstruction begins. They know the courts, procedures, archives, and codes, their expertise is as burdensome as it is indispensable during this transitional period. Yet their presence reminds Syrians daily of the ambiguities of the post regime period, how can justice be reformed when its actors served, willingly or not, a repressive machine ? How can a new system be built with those who worked in the shadows of the old one ? This is one of the most delicate knots of Syrian transitional justice, moving forward while the guardians of yesterday’s repressive apparatus still sit on the benches of the court.

The protection of witnesses is another deeply sensitive issue. Many still hesitate to share their stories for fear of reprisals. A Saydnaya survivor [56] confides, “I saw everything, but I cannot testify publicly. The militias who tortured me still live in my neighborhood. Who will protect me if I speak ?” These words reveal the lingering fear, but also the vital need to create safe spaces where survivors can speak without risking their lives. The collective narrative emerging from these accounts is not simply a chronicle of pain, it is an invitation to look at reality with renewed humanity and a promise of action.

The establishment of a truth commission is seen as a crucial step by those whose relatives disappeared and whose voices were long suffocated by fear. Abu Ahmed, survivor of the al Tadamon massacre whose brother was executed by the regime, speaks of a vital need, “Mass graves speak, but they are not enough. We need an official, recognized place where our stories will be written and where our dead will finally have a name.” It is a simple and deeply human request, to put names to lost lives so that families can begin to grieve and regain a measure of dignity. These words do not merely recount the sorrow of one family, they carry the collective memory of a nation still trying to understand what happened and to name what has disappeared.

Courts were not enough, and could never have been enough, given the scale of crimes and the immense number of victims. It is in this context that, in February 2025, the Syrian Truth Commission [57] was officially created, a space tasked with listening, documenting, and acknowledging what decades of violence had buried. For families, it represents the only chance to see recorded somewhere what official archives had sought to erase, the names of the dead, the stories of the disappeared, the voices of survivors. This commission is mandated to investigate violations committed by all parties, to reveal the structures that made repression and abuse possible, from secret prisons to chains of command, militias, and the progressive collapse of the rule of law.

It is designed as a bridge, a fragile but necessary bridge between victims and the state, between memory and justice, between mourning and the future. Its creation requires a clear mandate, real independence, reinforced protection for witnesses, and above all, the political will to accept that truth may be disturbing.

Abu Ahmed, survivor of the al Tadamon massacre whose brother was executed by the regime, speaks of a vital need, “Mass graves speak, but they are not enough. We need an official, recognized place where our stories will be written and where our dead will finally have a name.” It is a simple and human request, to put names to lost lives so that families can begin to mourn and regain a measure of dignity. Al Tadamon, Damascus, Syria, 26 September 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

Yet in a country where mass graves are still being uncovered and where families hang the portraits of their loved ones every day in the Tents of Truth, this commission appears as one of the few instruments capable of symbolically repairing what can never be fully repaired. It will not bring back the dead and it will not make the disappeared reappear, but it can offer Syria what it has lacked since 2011, a shared narrative, a collective memory, a first step toward breaking the imposed silence and restoring a central place to the victims in the history of the country. Syria, marked so deeply by these acts of violence, continues to move forward with a hope that is fragile yet persistent, the possibility of rebuilding what the war has destroyed, of giving a voice back to those who lost it, and of offering each person affected by the conflict a chance for dignity and recognition.

The outer wall of al Mujtahid Hospital in Damascus is covered with hundreds of portraits of missing persons and bodies undergoing identification Photo 1. Damascus, Damascus, Syria, 15 December 2024. For weeks, families rushed there hoping to recognize the face of a loved one abducted by the regime. In Saydnaya, hundreds of families remained for entire days after the prison was liberated, hoping to find traces of a relative taken by the regime Photo 2. Saydnaya, Damascus, Syria, 10 December 2024. Transitional justice often begins with a simple act, restoring a name, a story, and a burial place to the anonymous victims of barbarity. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

The Paths of Resistance

Beyond the courts, another form of justice takes shape in the shadows, carried by the families of the disappeared, the survivors of prisons, and Syrian civil society. Without official resources, often threatened and living in exile, these actors preserve memory and resist oblivion. Their actions form a cornerstone in the search for truth and justice. For more than ten years, thousands of families have demanded answers about the fate of their disappeared relatives, whether in the regime’s prisons, under Daesh, or after bombings. Transnational initiatives such as Families for Freedom [58] remind the world that the right to know is fundamental. The voices of survivors reveal a collective tragedy, and truth appears as a force capable of containing the desire for revenge and repairing the fractures opened by war.

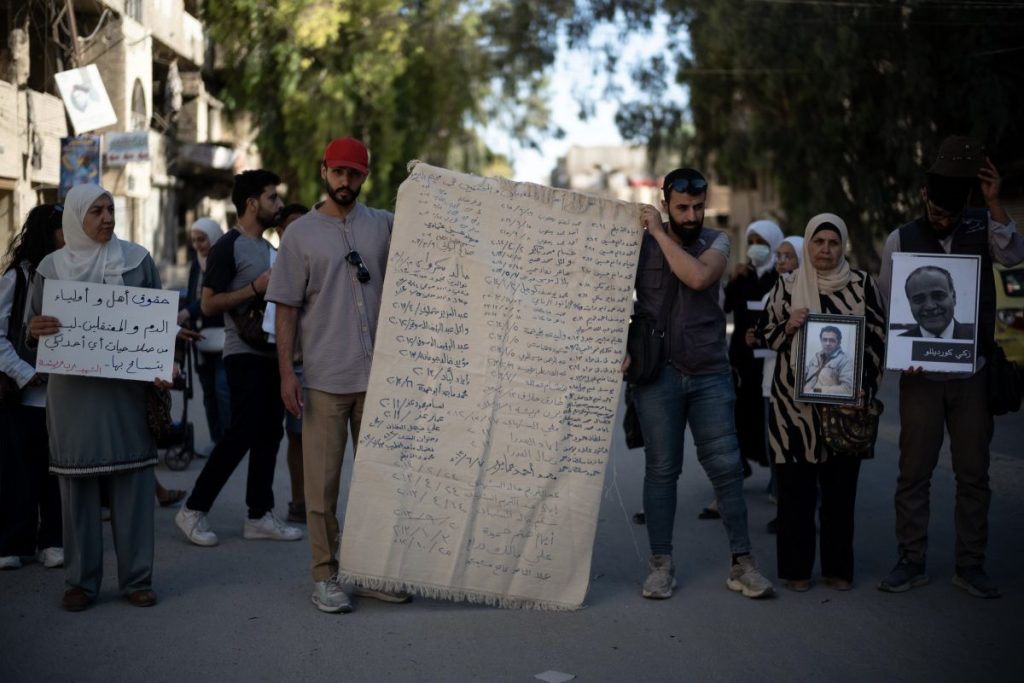

In 2016, as bombardments continued to plunge the population into mourning, the collective Families for Freedom emerged. It brings together mothers, sisters, and daughters of the disappeared. Wearing white scarves as symbols, these women traveled across European capitals to demand truth and justice. Their slogan, “No peace without our disappeared,” became a universal rallying cry. Amina Khoulani, one of the founders, stated during a conference in Brussels, “We are not mere victims. We are the guardians of memory and we refuse to let the world forget our loved ones.” Other collectives are multiplying initiatives to preserve shared memory. The Tents of Truth, set up in Jaramana [59] and Yarmouk, are not only places of commemoration, they are spaces where stories are heard, stories at risk of fading in the noise of official narratives and general inaction. These modest structures, often improvised and without institutional support, break the silence weighing on families. For Iyad Al Shaarani, these tents carry a promise, “They are not only places of memory, they are the first court of the people. Each testimony is a piece of evidence, each photo an indictment.” The voices of survivors transform memory into action and nourish the hope that pain can be turned into protection for the most vulnerable.

Syria could consider a mixed approach adapted to its reality, local truth and memory commissions to document crimes, national and international trials to prosecute those responsible, and community dialogue spaces inspired by Syrian practices and mechanisms such as the Gacaca. Their success, however, will depend on political will and the effective inclusion of victims. In Jaramana, Amani Abboud, a former political prisoner, seeks answers rather than revenge, she wants to know where her brother is and what happened to him. She believes that justice is not limited to a distant court such as The Hague, the disappeared must be found, given a burial, and allowed to be mourned. Iyad Al Shaarani insists on the importance of officially inscribing the voices of victims in the archives and judicial decisions, transitional justice depends on transforming individual pain into collective recognition.

Organizations such as SCM Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression [60] and SNHR Syrian Network for Human Rights [61] document violations to support future trials, their archives give identities and voices to those awaiting justice. International experiences show the impact of public testimony on collective healing. Memory is essential for identity and reconciliation. The Mothers of Srebrenica, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa placed the testimony of victims at the center of the process. Fabian Salvioli, Argentine jurist and human rights expert, former president of the UN Human Rights Committee, stresses that “the right to truth, justice, and reparation is universal.” The memory of disappeared relatives is tied to identity, and transitional justice depends on the ability of society to build a shared memory.

Amani Abboud, a former political prisoner and an activist within the Jaramana Tents of Truth, is seeking answers rather than retaliation, she wants to know where her brother is and what happened to him. Jaramana, Damascus, Syria, 21 April 2025 © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

The organisation NoPhotoZone and local action play a concrete role in activating this memory. This initiative, founded by Syrian activist and lawyer Noura Ghazi, illustrates this locally rooted dynamic shaped by the diaspora and strengthens the voice of families, particularly mothers and relatives of detainees. According to Noura Ghazi, “Transitional justice must begin at the local level, in communities, with everyday narratives.”

NoPhotoZone is a space where they can tell their story, understand their rights, and find a place within society. Noura Ghazi is also a member of Families for Freedom, alongside Amina Khoulani and Wafa Mustafa. She also highlights the fundamental role of women in this process, “Syrian women have carried everything on their shoulders. They were the first to suffer from the war, to lose their husbands, their sons, their homes. But they are also the ones who kept their families standing, who kept the children alive, who searched for the truth when no one else dared to do so. Yet in decision making processes, they are almost never heard. Women must be at the heart of reconstruction, not at its margins. They have a legitimacy no one else has, because they lived the war from the inside.”

The work is difficult, marked by shame, mourning, and insecurity, but these voices feed a shared memory and prepare the ground for more just transitions. On the legal and documentary level, Syria illustrates the limits of international law in the face of mass crimes, many resolutions linked to the conflict were blocked, delaying the action of the ICC. The universal right to truth, justice, and reparation remains, when international jurisdictions are paralysed, national jurisdictions take over. The CIJA Coalition for International Justice in Syria [62] has collected more than 800000 official documents, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and groups such as Caesar Families [63] and the Tents of Truth have gathered thousands of testimonies and visual evidence, the IIIM holds millions of digital pieces of evidence. This documentation is essential to counter the erasure of war crimes and crimes against humanity and of the victims themselves.

For more than ten years, millions of Syrians have been forced to flee, finding refuge in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and in Europe and North America. The Syrian diaspora plays a crucial role in the struggle for justice, associations, networks of survivors, and legal groups in exile document crimes, collect testimonies, and carry the voices of victims onto the international stage. Wherever they mobilise, they remind the world that the memory of the conflict cannot be erased. Iyad Al Shaarani states that the diaspora is “the guardian of a collective memory the regime tried to annihilate.” This mobilisation has also triggered legal advances beyond Syrian borders. In response, several European states have resorted to universal jurisdiction [64], in Germany, the Koblenz trial 2020 to 2022 convicted Anwar Raslan for crimes against humanity, marking a major step. In France, the efforts of organisations in exile have supported investigations leading to arrest warrants for Bashar al Assad and other officials. Although partial, these victories show that transitional justice can extend beyond national boundaries.

The Families for Freedom campaign portrays the agony and struggle of all Syrian families who have suffered the loss or disappearance of a loved one in detention. The women of the collective continue their efforts to include as many families as possible, regardless of their religious sect, so that the truth may be established about the fate of their missing relatives and justice may be achieved. Al Marjeh Square, Damascus, Damascus, Syria, 25 May 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMedia.

In parallel, the diaspora develops cultural and memorial initiatives to preserve history through human narratives, including exhibitions, plays and documentaries that give a voice to individual tragedies. In the absence of an official process in Syria, it has become a bulwark against oblivion and seeks to connect an atrocious past to a future yet to be rebuilt. Digital platforms run by the diaspora such as SyriaUntold [65] or Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution [66] sustain a living memory by transmitting stories, artistic works and testimonies across generations.

Films such as For Sama (2019) directed by Waad al Kateab and Edward Watts which follows the life of a young Syrian mother in Aleppo during the civil war, The Cave (2019) directed by Feras Fayyad which is an immersive documentary on an underground medical clinic led by Dr Amani Ballour in the eastern Ghouta of Damascus and on the organisation of medical care under precarious conditions and the work of doctors and medical staff, The White Helmets (2016) directed by Orlando von Einsiedel which is an observational documentary on the daily life of the White Helmets Civil Defense in Syria highlighting their rescue operations in bombed areas and the risks they face, Last Men in Aleppo (2017) directed by Feras Fayyad which is a field documentary and a collective portrait following a group of residents activists and White Helmets in Aleppo over an extended period illustrating the harsh reality of urban combat and humanitarian operations with direct testimonies, or City of Ghosts (2017) directed by Matthew Heineman which is a journalistic documentary about a group of Syrian American citizen journalists documenting life in Raqqa under IS control and the humanitarian consequences with an immersive investigative approach and a focus on the role of citizen media in wartime, are all essential pieces of evidence and memory that must be preserved to serve transitional justice.

Ulrike Capdepón [67] reminds us that memory has become “an essential pillar of the debates and practices of transitional justice” [68] and stresses that “judicial initiatives and memorial initiatives are deeply interconnected and reinforce one another” [69].

Douma in the eastern Ghouta near Damascus was the scene of numerous chemical attacks carried out by the Syrian regime. Hundreds of civilians were injured and killed, triggering a strong international reaction and investigations conducted by the UN and the OPCW Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. The underground hospital in Douma photo 1, 2 stands as a remnant of these crimes and as a witness to how civil defense teams tried to save as many victims as possible with no resources and at the risk of their lives. The portraits of the martyrs of the chemical attack of 1 April 2018 still adorn the entrance of the targeted building to ensure they are not forgotten photo 4. Douma, Eastern Ghouta, Syria. 28 April 2025. © Audrey M G, SpectoMédia.

Today, now that the Assad clan regime is gone, the media continue to play a central role in this process. Their mission is no longer limited to documenting the crimes, they must also transmit, contextualize, and help transform collective perception. Syrian activist Amani Abboud highlights the essential stakes of this work, “Without shared memory, justice has no meaning. Testimonies, images, stories, all of this must be passed on to new generations so that they do not repeat the mistakes of the past.” The combined work of journalists, citizen collectives, and documentation NGOs builds a plural memory that attempts at erasure cannot destroy. Whether in Syria, Argentina, Bosnia, or Germany, the transmission of this memory conditions the very possibility of achieving justice.

From the first mobilizations in Deraa in March 2011, independent media and citizen journalists were decisive. With simple phones, they captured the repression and circulated these recordings, breaking the narrative monopoly of the regime. Without them, massacres such as Houla, Daraya, Aleppo, and the siege of Yarmouk would likely have been forgotten. This visual documentation fed crucial archives for transitional justice, even as memory was contested by the regime and its allies.

The conflict turned into a battle of narratives and propaganda. Archives and data play a key role, the Syrian Archive [70] catalogs and verifies millions of videos and documents, the SNHR records victims and missing persons, the Caesar Files Group [71] gathers testimonies and evidence that support investigations. These resources have been decisive in international trials, reinforcing direct testimonies, photographs, and organizational reports. In Beirut, journalist Hadi Abdullah stresses that without images and stories, the regime would have buried the truth with the victims.

In Syria, memory is not limited to archiving, it guides prosecutions, gives victims a voice, and shapes public perception. Amani Abboud reminds us that transmitting this memory gives meaning to justice and prevents new generations from repeating past mistakes. Engaging with testimonies and archives makes it possible to transform personal narrative into shared memory and symbolic acts into concrete justice. The speed and credibility of the process will determine its legitimacy and its impact on Syrian society, in order to prevent the history of the disappeared from being forgotten and the cycle of violence from repeating.

Amani confides, “What scares me the most is that the story of my disappeared brother will be forgotten. If we do not tell it, the regime will have won twice, by killing him and by erasing his memory.”

Media, collective memory, and diaspora networks are therefore essential levers of transitional justice in Syria. They sustain truth, legitimize future procedures, and ensure that victims voices do not fall into oblivion. This documented memory has already taken shape in trials and continues to inform investigations and political actions. However, justice cannot be complete without a presence on Syrian territory. As Pablo de Greiff, Colombian expert on transitional justice and first United Nations Special Rapporteur on truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of non repetition, has emphasized, diasporas emerging from conflicts have an important role to play, but transitional justice mechanisms must be rooted first and foremost in the country where the crimes were committed, so as to rebuild the social fabric and restore trust. [72]

National Reconciliation

Syria cannot pursue its transitional justice in isolation, it must rely on external reflections and draw lessons from neighboring countries. Hadeel Abdel Aziz, director of the Justice Center for Legal Aid [73] in Amman, recalls that judicial reforms must build on foreign experiences without reproducing them mechanically and recommends inspiring and innovating [74]. In Syria, this implies building a hybrid model, adapted to sociopolitical and community realities, rather than importing ready made solutions. Maha Yahya, expert at the Carnegie Middle East Center [75], illustrates the dangers of general amnesty, the amnesty law adopted in Lebanon after 1990 allowed militia leaders to reinvent themselves as political officials, while erasing the memory of the war and preventing any public debate on the crimes committed. This model fostered a profound lack of trust and persistent corruption. Syria must avoid this trap [76]. The legacy of this amnesia is still deeply felt in Lebanon, notably through a deficit of citizen trust and deeply rooted corruption. For Maha Yahya, Syria will have to avoid falling into this trap by adopting a different approach that does not sacrifice either collective memory or the demands for justice.

Lebanon, a counter example of transitional justice. The adoption of the amnesty law after 1990 allowed militia leaders to reinvent themselves as political officials, while erasing the memory of the war and preventing any public debate on the crimes committed. This model fostered a profound lack of trust and persistent corruption. Beirut, Lebanon. 8 November 2022. © Audrey M G, SpectoMédia.

Iyad Al Shaarani also highlights the importance of the regional context as a source of learning. According to him, the examples of Syria’s Arab neighbors offer valuable lessons about what must be avoided at all costs. He firmly argues that Syria now stands before a unique opportunity, to prove that an Arab country is capable of looking at its own history with transparency, “Our neighbors show us what must not be done. Syria has a rare opportunity to demonstrate that an Arab country can confront its past with transparency, by listening to the victims and refusing compromises with criminals.” Lebanon chose oblivion and Jordan chose stability at the expense of structural reforms. Syria must choose between temporary amnesia and a difficult but necessary process of justice and reconciliation, which requires listening to victims narratives and confronting the truth.

For traumatized families, reconciliation requires truth, a mother from Hama asks, “the forgiveness they ask for is meaningless if the disappeared are not located. How can we speak of reconciliation without truth ?” CIJA insists, “without memory and documentation of past crimes, any reconciliation process is built on denial.” International lessons show a common dilemma, in South Africa, truth and reconciliation opened national dialogue but with controversial amnesties, in Rwanda, the Gacaca courts offered local appeasement while sometimes fueling resentment, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Dayton Accords ended the fighting but froze divisions, in Argentina, the junta trials and memory policies demonstrated the importance of the interconnection between justice and memory.

Beyond judicial dimensions, the psychological scars are profound. Doctors Without Borders [77] and the Syrian Center for Policy Research [78] show that more than half of Syrians suffer from trauma, a former Saydnaya detainee explains that after his release, he cannot meet the eyes of his neighbors and must learn to live again. Paulo Pinheiro, president of the United Nations International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, mandated to document serious violations committed since 2011, reminds us that without truth and justice, speaking of reconciliation would be illusory, yet an imperfect reconciliation remains indispensable to inhabit once again a shared destiny. Noura Ghazi notes, “Today in Syria, we have no elected authority, no normal situation. We hear speeches, but no concrete action. Victims have immense needs at every level, and nothing is being done to meet them.” She specifically mentions the situation of former prisoners, “They need rehabilitation, reintegration into society, psychological support. Nothing is planned in this regard.” Without concrete action by the new authorities and without a genuine willingness to place victims and their families at the center of this transitional justice process, national reconciliation cannot occur.

Syria must therefore consider a combination of approaches, local truth and memory commissions, national and international trials, and community dialogue spaces inspired by Syrian practices and mechanisms such as the Gacaca, while ensuring genuine inclusion of victims. As neighboring experiences indicate, reconciliation without memory or accountability is unsustainable, this ambitious objective could become not only a model for the region but also a decisive step toward a more just and resilient society.

Among the most delicate and decisive areas of transitional justice in Syria is education. After more than a decade of war marked by mass displacement, the destruction of schools, and interrupted learning paths, the challenge goes far beyond simply reopening classrooms or providing textbooks. What is at stake is the choice of the collective memory that will be transmitted to future generations. In some areas, children have known only war and exile, while others grew up under the regime’s influence, with textbooks glorifying its authority while omitting the crimes committed. This memory gap has serious consequences. If ignored, it risks reproducing in schools the deep divisions that fueled the conflict.

As Francesco Bandarin, former UNESCO culture official [79], has often emphasized, history textbooks are never neutral and, if they conceal or distort the atrocities committed, they risk fueling new cycles of violence, “History education must help understand the root causes of conflicts, recognize suffering, and contribute to preventing violence from recurring.” [80]. Lawyer Iyad Al Shaarani stresses the importance of immediately integrating into education the truth about enforced disappearances, torture, and mass graves, so that young Syrians can fully understand the legacy of the past.

According to him, “education must be the first antidote against denial.” A request also made by Um Karam, met in Darayya in October 2025, whose two husbands were detained in Saydnaya, “There has not been as much darkness or oppression in other countries as what we have endured here in Syria.” She adds, “In history books, everything must be told. It is essential that our children know the truth about what happened. The whole world as well.”

International experiences show that education plays a central role in reconciliation. In Rwanda, after the 1994 genocide, the authorities removed ethnic references from school curricula while introducing courses on national unity and genocide prevention. This process helped reduce some forms of stigmatization, although some experts criticized the standardization of the official narrative. In post apartheid South Africa, history teaching was deeply revised to include victims testimonies and encourage a national identity based on diversity and democracy. Bosnia offers a cautionary example of educational fragmentation, to this day, Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks follow parallel school systems with radically different textbooks. This approach, known as “two schools under one roof”, is often cited as a model to avoid.

A recent report by the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) [81] stresses that education in a post conflict context must not be reduced to a technical operation. It must become a space for dialogue on human rights, plural memory, and citizenship. Rebuilding Syria also means rebuilding consciences. It is essential to teach children not only what happened, but why it must never be repeated. Many Syrian actors therefore advocate the introduction of programs inspired by the Argentine experience, in this framework, survivors speak in schools to share their testimonies. These living narratives transform facts into an embodied and accessible memory.

For Noura Ghazi, this transmission also requires recognizing the role of youth, “Yes, it is a tired generation, but also a courageous one. Many grew up amid fear, bombs, propaganda. They have known neither stability nor freedom. And yet, some of them still seek to understand, to act, to learn.” She adds with conviction, “They are the future. Not the old politicians, not those who have already failed. Young people are capable of inventing another way of thinking about justice, less bureaucratic, more human.” She also stresses the importance for victims to understand what transitional justice is and what their rights are, and for young people to learn from the experiences of other countries in order to build citizenship based on memory and empathy.

Ultimately, Syria’s educational future goes far beyond the school system. It relies above all on the ability of Syrian society to confront its past in order to turn it into a foundation for citizenship and social cohesion. Without a collective effort to make education a tool of reconciliation, today’s divisions risk persisting among future generations.

Annexes

[35] In the rural areas of Latakia and Sweida, recent violence shows that former security networks and regime militias continue to control the ground. Around Latakia, Reuters documented more than one thousand civilians killed in coordinated massacres in 2025,

https://www.reuters.com/investigations/syrian-forces-massacred-1500-alawites-chain-command-led-damascus-2025-06-30/

and HRW recorded kidnappings and assassinations targeting Alawites,

https://www.hrw.org/report/2025/09/23/are-you-alawi/…

In Sweida, Amnesty revealed the execution of at least 46 Druze civilians in July 2025,

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/09/syria-new-investigation…

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/09/syria-new-investigation

while Le Monde described a city abandoned to the “fouloul”, the remnants of the regime,

https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2025/07/26/syria-after-druze-killings…

[36] The moukhabarat refers to the Syrian intelligence services, known for their central role in surveillance, repression, and population control under the Assad regime.

[38] Wafa Mustafa is a Syrian journalist and activist engaged in the fight against enforced disappearances. Her father, Ali Mustafa, was abducted by Syrian security services in 2013, which forced her into exile and made the struggle for truth and justice her central cause. Based in Germany, she campaigns within the Free Syria’s Disappeared coalition, testifies before the UN, and participates in international justice initiatives documenting the crimes of the Assad regime. She has become one of the most visible and important voices of the families of the disappeared.

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2025/oct/02/hope-duty-not-emotion-fight-syria-disappeared-assad-regime-must-go-on?

[39] The International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) is a UN body responsible for collecting, analyzing, and preserving evidence of the most serious crimes committed in Syria since 2011, in order to support future prosecutions before national or international courts.

[40] Noura Ghazi is a Syrian lawyer and human rights defender specializing in arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance. She is the founder of NoPhotoZone, an organization created in memory of her husband, open source developer Bassel Khartabil, executed by the Syrian regime. NoPhotoZone documents violations, supports families of detainees and the disappeared, and promotes justice and truth in Syria.

[41] A forensic plan is a precise and documented diagram reconstructing an event, crime, attack, or scene of violence using material, visual, or digital elements to clarify its unfolding and support judicial analysis.

[44] The Srebrenica massacre refers to the execution of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in July 1995 by Bosnian Serb forces after the fall of the Srebrenica enclave, despite its status as a UN “safe area”. It is the worst crime committed in Europe since World War II and has been recognized as genocide by international courts.

[45] Yarmouk, in Damascus, is a large district of Palestinian origin that became one of the most tragic symbols of the Syrian war. Besieged from 2013 to 2015, it suffered famine, bombardment, and intense fighting, leading to its near destruction and to the exodus of most of its inhabitants.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/oct/26/little-palestine-diary-of-a-siege-review-refugee-camp-yarmouk-syria

[46] Mazen al Hamada was a Syrian activist arrested in Syria for protesting. After a year and a half of detention, he managed to flee in 2014. A survivor of torture, he became a major voice denouncing crimes committed by the Assad regime’s intelligence services. Returning to Syria in 2020, he immediately disappeared. After the fall of the regime, it was confirmed that his body had been found in the morgue of the Damascus military hospital, proving he had again been arrested and died in detention.

https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/14431463

[47] In post war Syria, as families still search for their disappeared, the Tents of Truth have become places where pain turns into collective action. Under these tents in Ghouta, Yarmouk or Deir al Asafir, mothers, brothers, and children hang portraits of the missing, recount what happened to them, and demand at last to know where their loved ones are. These simple yet emotionally charged spaces break years of imposed silence, people speak of detention, torture, mass graves, as well as dignity, future, and justice. For many, these tents are the first place where they can publicly tell their truth, and where Syrians, across communities and divisions, begin to rebuild a shared memory.

https://www.ungeneva.org/fr/news-media/news/2025/05/106064/en-syrie-la-lente-quete-de-verite-pour-les-familles-des-disparus

[48] Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non governmental organization that investigates human rights abuses worldwide, publishes detailed reports, and advocates for justice and accountability.

[49] The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP) is the investigative commission created in Argentina in 1983 to document enforced disappearances committed under the military dictatorship and to produce the official report Nunca Más, which later served as the basis for judicial prosecutions.

[50] Human Rights Watch, Saydnaya (2015), Syria: Secret Detainees at Risk

https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/14/syria-secret-detainees-risk

[51] Amnesty International, Enforced Disappearances (2015), Between Prison and the Grave: Enforced Disappearances in Syria

[52] The Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) is an independent organization that collects, verifies, and analyzes evidence of violations committed in Syria to support investigations, judicial prosecutions, and transitional justice mechanisms.

[53] Syrian Justice and Accountability Centre, Tadmor (2020), Inside Tadmor: Stories of Survivors

https://syriaaccountability.org/inside-tadmor-stories-of-survivors

[54] The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is the UN body responsible for promoting and protecting human rights worldwide, monitoring violations, supporting victims, and helping states meet their international obligations.

[55] OHCHR, Report of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Human Rights Situation in the Syrian Arab Republic, 2025

[56] Saydnaya is one of countless Syrian military prisons, considered one of the most brutal under the Assad regime. According to an Amnesty International report, it functioned as a genuine “human slaughterhouse”, where torture, hangings, executions, and enforced disappearances were carried out in a systematic, organized, and massive manner.

https://www.amnesty.org/es/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2021/05/MDE2454752017FRENCH.pdf

[57] A Truth Commission is an official, usually temporary, body tasked with investigating past serious human rights violations, collecting victims testimonies, and producing a public narrative to acknowledge wrongdoing, establish responsibilities, and foster reconciliation.

[58] Families for Freedom is a Syrian civic movement, founded and led mainly by women whose relatives were disappeared or detained, advocating for truth, justice, and the release of all arbitrarily detained persons. Since the fall of the regime, the movement plays a central role in identifying the disappeared, defending families rights, and participating in transitional justice mechanisms, including truth commissions and institutional reform processes.

[59] Jaramana is a densely populated suburb southeast of Damascus, known for its diverse Druze and Christian communities and for having hosted many internally displaced people during the Syrian war.

[60] The Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM) is an independent Syrian organization documenting human rights violations, defending press freedom, supporting victims of detention, torture, and enforced disappearance, and contributing to international justice and accountability mechanisms.

[61] The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) is a documentation organization that records and analyzes serious violations committed in Syria since 2011, executions, massacres, chemical attacks, detentions, disappearances, and produces reference reports used by the UN, international courts, and NGOs to establish responsibility and support justice.

[62] The Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) is an independent organization that collects, analyzes, and preserves evidence of international crimes committed in Syria, including official regime documents, to support investigations and prosecutions before national or international courts.

[63] Caesar Families is a collective of Syrian families whose relatives appear in the photographs of detainees tortured and killed in the regime’s prisons, images leaked by the whistleblower “Caesar”. The group advocates for truth, identification of victims, justice, and official recognition of the crimes committed in detention.

[64] Universal jurisdiction is a legal principle allowing a state to prosecute perpetrators of the most serious crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, even if these crimes were committed abroad, by foreigners, and against foreigners.

[65] SyriaUntold is an independent platform for journalism and storytelling that documents the social, political, and cultural histories of the Syrian revolution, giving voice to activists, artists, local communities, and citizen initiatives.

[66] Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution is an archival project that collects, preserves, and publishes artistic and cultural expressions produced since 2011, drawings, videos, slogans, graffiti, songs, stories, to keep alive the creative memory of the Syrian revolution.

[67] Ulrike Capdepón is a researcher specializing in transitional justice and memory politics, whose work focuses on Spain and Latin America. She studies how societies emerging from authoritarian pasts use memory, justice, and accountability to rebuild social and democratic cohesion.

[68] Transitional Justice and Memory in Spain, The Politics of Remembering, 2017

[69] Transitional Justice, Memory, and Human Rights in Spain, Journal of Human Rights Practice, 2016.

[70] Syrian Archive is an organization specializing in collecting, verifying, and preserving digital content related to human rights violations in Syria, photos, videos, recordings, to document crimes, support judicial investigations, and protect threatened evidence.

[71] Caesar Files Group is a Syrian collective dedicated to identifying, verifying, and publishing the thousands of photographs of victims who died under torture in regime prisons, images leaked by the whistleblower “Caesar”. The group supports families in their search for truth and contributes to international investigations into detention crimes.

[72] Promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non repetition, October 2016

https://docs.un.org/fr/A/71/567

[73] The Justice Center for Legal Aid (JCLA), based in Amman, is an independent Jordanian organization providing free legal assistance to vulnerable persons, refugees, women, children, low income workers, and defending their access to justice through legal advice, representation, and rights awareness.

[74] Hadeel Abdel Aziz, interventions on adapting judicial reforms to the local context, Justice Center for Legal Aid (JCLA), Amman.

[75] The Carnegie Middle East Center is a research center based in Beirut, part of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, producing independent analysis on political, economic, and social dynamics in the Middle East, particularly on conflicts, transitions, and governance issues.

[76] Maha Yahya, Let the Dead Be Dead, Communal Imaginaries and National Narratives in the Post–Civil War Reconstruction of Beirut, in Urban Imaginaries, Locating the Modern City, ed. A. Çınar and T. Bender, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

https://epdf.pub/urban-imaginaries-locating-the-modern-city.html

[77] Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is an international humanitarian organization providing emergency medical care to populations affected by conflict, epidemics, natural disasters, or lack of access to health services, in full independence and impartiality.

[78] The Syrian Center for Policy Research (SCPR) is an independent research center analyzing the economic, social, and political impacts of the Syrian conflict, producing data based studies and policy recommendations supporting reconstruction, social cohesion, and sustainable development.

[79] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), a UN agency promoting education, culture, science, and freedom of expression to strengthen peace, protect heritage, and support international cooperation.

[80] UNESCO, Holocaust Education and Genocide Prevention, A Policy Guide, 2017

[81] The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) is an international organization assisting societies emerging from conflict or authoritarian rule in establishing transitional justice mechanisms, truth, justice, reparations, and institutional reforms, in order to fight impunity and rebuild civic trust.