Between Chaos and Abandonment : The Psychological Devastation of Endless Conflicts

« …I don’t know what we did to deserve this kind of humiliation…

But what’s certain is that we keep on living, despite everything…

And that, in itself, is a form of resistance. »

Ziad Rahbani

Prolonged armed conflicts produce long-lasting, profound, and often invisible psychological consequences within civilian populations. In contexts such as Gaza, Sudan, or eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), repeated violence, loss of reference points, forced displacement, and the destruction of healthcare infrastructures contribute to a collective psychological breakdown. Though difficult to quantify, this phenomenon is well-documented in medical and humanitarian literature. These situations unfold in wartime dynamics where mental health is relegated to the background—despite being a crucial factor for survival, resilience, and social reconstruction.

Long-Term Psychological Distress: Gaza, Sudan, and the DRC—Three Major Conflicts with Invisible Suffering

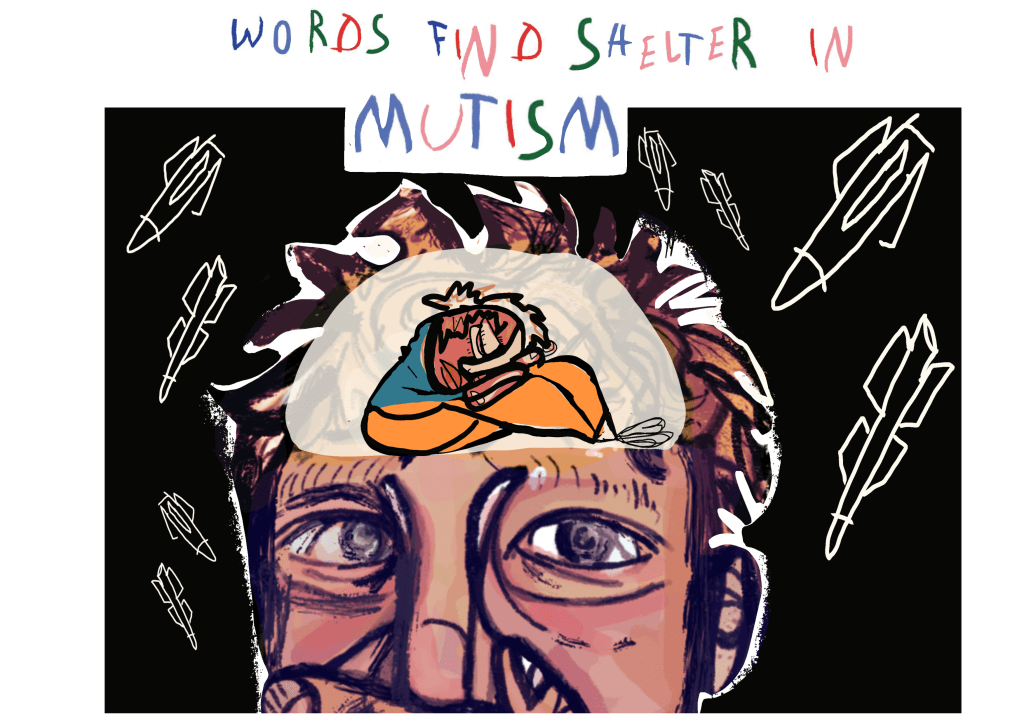

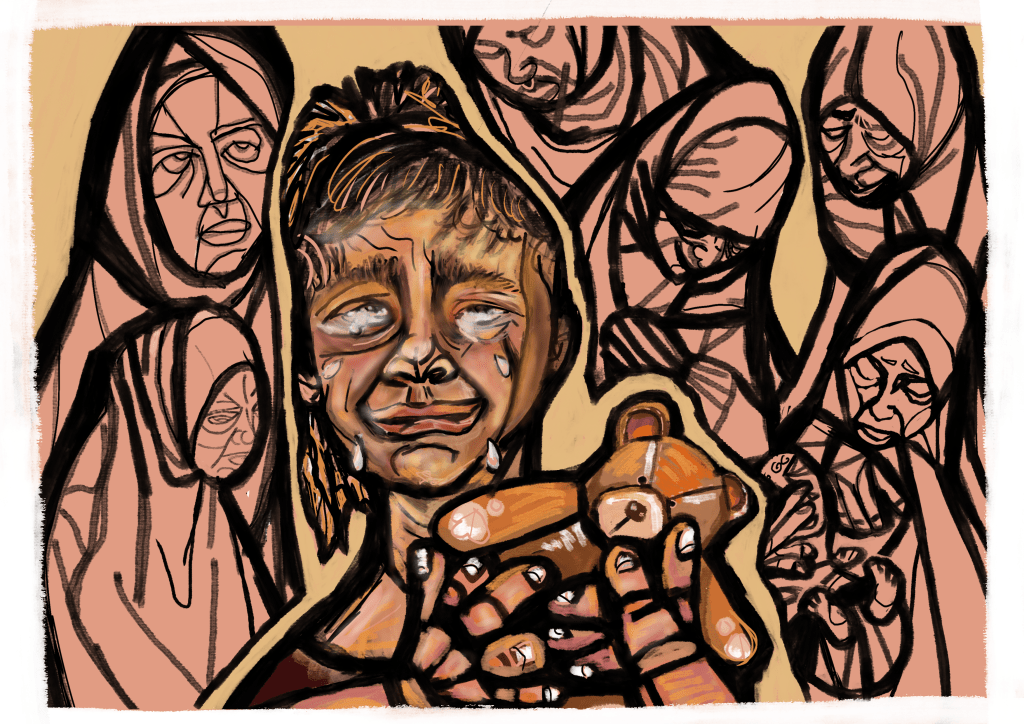

In Gaza, the ongoing genocide since October 2023 has plunged the population into a prolonged state of shock. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reports that over 1.9 million people have been internally displaced within a population of 2.3 million, worsening precariousness and psychological instability (UN OCHA, 2024). According to a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) report (2024), health professionals describe widespread mental distress marked by symptoms of post-traumatic stress, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, and emotional numbness. Children—particularly vulnerable—exhibit alarming signs of sleep disorders, aggression, or mutism. “Families have lived under bombardment for months, with no rest and no hope of returning to a normal life. How can a human mind endure such continuous pressure?” wonders a local psychologist cited by MSF (2024).

In Sudan, the civil war between the regular army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has led to a brutal collapse of the social order. According to Amnesty International (2025), over 12 million people, mostly women, are now exposed to sexual violence in a context also marked by destroyed medical infrastructures and mass displacement (over 9 million internally displaced). A recent study published in BMC Psychology (2024) found that 64% of people surveyed in conflict zones displayed at least one symptom of post-traumatic stress, and 38% suffered from severe anxiety disorders. While incomplete, these figures highlight the vast scale of collective trauma driven by security collapse and lack of humanitarian protection. Women are particularly affected, often victims of gender-based violence, with deep psychological repercussions and little support.

In the DRC, two decades of ongoing armed conflict in the eastern provinces have resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. Since January 2025, over 7,000 people have been killed in North and South Kivu alone, and more than 700,000 displaced in just a few months. According to the International Rescue Committee, between 1998 and 2007, some 5.4 million people died due to the conflict, now exceeding 6 million by various humanitarian counts—making this one of the deadliest crises since World War II. Reports from Amnesty International and the UN Human Rights Council regularly document massacres of civilians, systematic wartime rape, forced displacement, and the recruitment of child soldiers. This context leads to what researcher Kasereka Bindu (2021) calls a “normalization of terror,” where psychological suffering becomes silent, internalized, and potentially passed on across generations. Transgenerational trauma manifests as an invisible transmission of psychological distress to children and grandchildren of survivors, affecting family dynamics, collective memory, and self-perception. WHO estimates that 2.2 million people suffer from severe mental disorders in the DRC, but fewer than 2% have access to any form of specialized care (WHO, 2023).

Deep but Hidden Psychological Effects

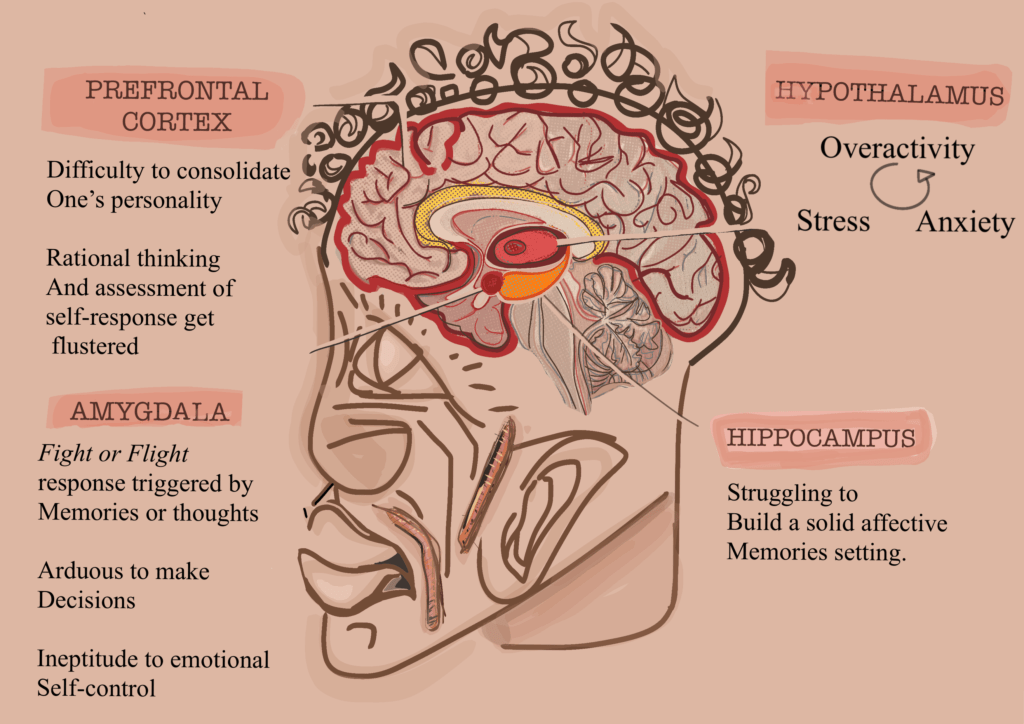

War-related trauma doesn’t always manifest through classic psychiatric symptoms. Many researchers highlight the importance of silent suffering, often somatic or masked within cultural contexts where mental health remains stigmatized (Rousseau & Drapeau, 2003). In prolonged war zones, psychological disorders may appear as chronic pain, behavioral issues, avoidance, or emotional withdrawal. The psyche retracts, dissociates, and tries to survive in a perpetually unsafe environment.

In his work on war trauma, Australian psychiatrist A. Silove (1997) speaks of a « triple rupture » caused by armed conflicts: rupture of the social fabric, geographic rupture, and rupture of psychic continuity. These lead to a collapse in perception of time, memory, and the capacity to symbolize traumatic experience. In Gaza, for instance, some children under ten have lived through more than five wars without ever knowing lasting peace. This reality profoundly alters their emotional and relational development, with potentially lifelong effects on their relationship to themselves and the world.

War does more than wound bodies, it fractures imagination, bonds, and the ability to hope. In conflict zones, trauma becomes systemic, a social pathology as much as an individual one. Researcher Julie Chapon writes: “It is not only an accumulation of psychic wounds but a collective collapse of subjectivity” (The Conversation, 2024). This suffering, though immense, remains barely visible in international media and even less addressed in emergency humanitarian responses. What, then, will become of these children once they grow up, forced to rebuild themselves without guidance or a sense of security?

An Absent Psychological Response

Despite the severity of this distress, mental healthcare systems are largely inadequate. In Gaza, mental health facilities have been destroyed or shut down. According to MSF (2024), it is now nearly impossible to offer long-term psychological support due to a lack of safe spaces, materials, or qualified personnel. Local psychologists themselves are affected by collective trauma, working under extreme conditions without supervision or respite.

In Sudan, the situation is even more dire: nearly all psychiatric hospitals have closed, and the few NGOs operating face insecurity, mass displacement, and chronic underfunding. A survey by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect (2024) revealed that fewer than 5% of survivors of extreme violence receive psychological support and only 1% in rural areas.

In the DRC, local initiatives like those of the Panzi Foundation aim to provide integrated psychological care for survivors of sexual violence. However, these efforts are limited geographically and cannot meet the vast population’s needs. The lack of a national mental health policy, combined with structural poverty in the health system, makes sustainable mental health strategies nearly impossible. This lack of access to mental health services isn’t just logistical, it’s compounded by media indifference, where collective suffering struggles to find a place in the global public sphere.

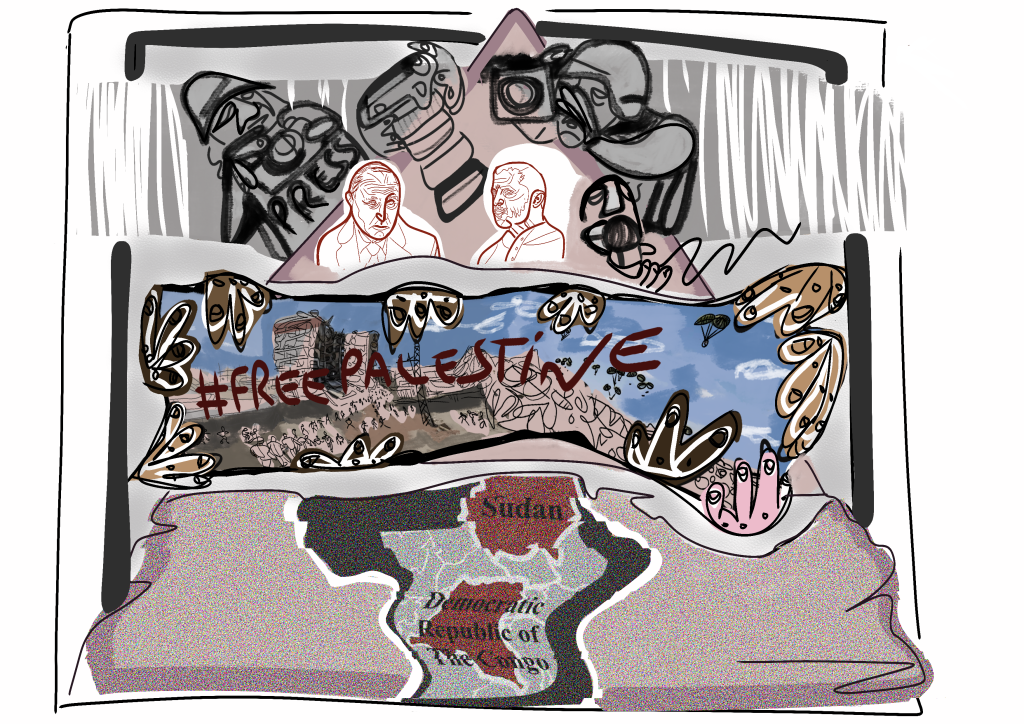

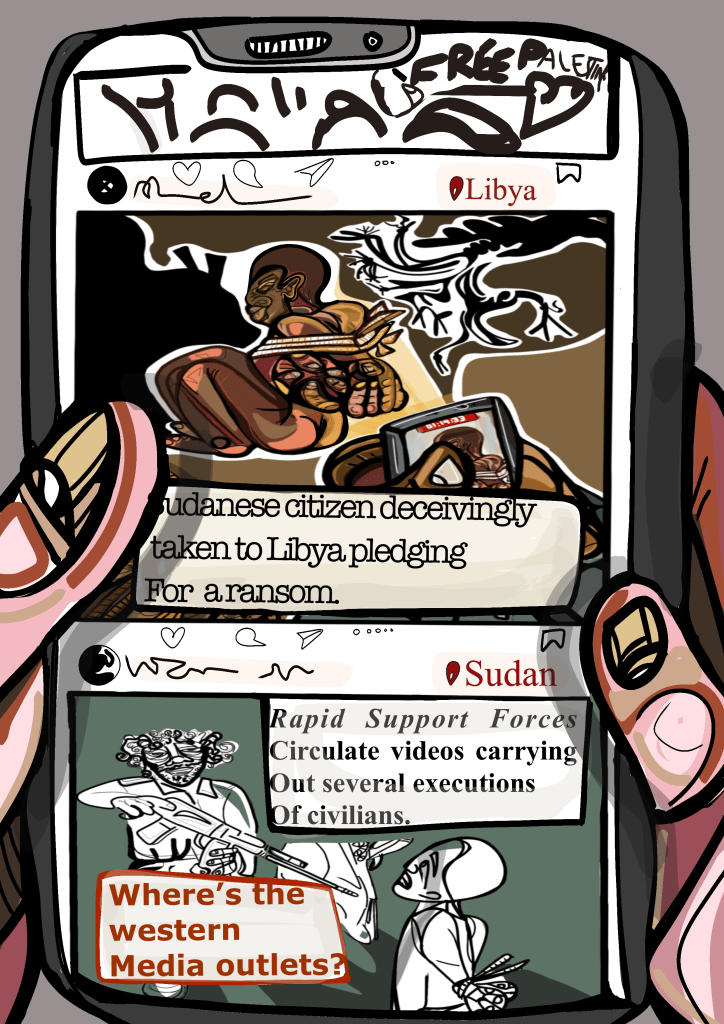

Information Overload and the Hierarchy of Tragedies

While the prolonged conflicts in Gaza, Sudan, and the DRC produce extremely grave human consequences, they don’t all receive equal attention in media or international public discourse. This disparity highlights a dual problem: on one hand, content saturation and accelerated news cycles fragment collective attention; on the other, not all conflicts are treated equally, revealing an implicit hierarchy of tragedy. These two dynamics information overload and unequal visibility contribute to the psychopolitical invisibility of some forms of suffering.

Attention Fatigue: The Impact of Information Overload

The digital age is marked by a constant, immediate, and often uncontrolled flow of information. This phenomenon coined “information obesity” refers to cognitive overload, where people are bombarded with excessive data, images, and stories with little context or prioritization. According to Frontiers in Psychology (Wang et al., 2023), this overload correlates with higher anxiety, mental fatigue, and reduced ability to retain or prioritize collective issues.

In conflict reporting, this saturation impairs emotional and political engagement. The longer violence persists, the more attention wanes. Studies on “compassion fatigue” show that repeated horror, instead of mobilizing action, often leads to moral numbness. Human attention is a finite resource, it disperses, tires, and collapses under endless scrolling. As philosopher Bernard Stiegler explained, the « attention economy » reduces our engagement with the world to brief impulses captured by algorithms, where emotion overrides reflection (Stiegler, 2004). Statistics confirm this: according to the Reuters Digital News Report 2024, over 38% of users actively avoid the news, citing it as “too negative,” “too repetitive,” or “too distant.” This informational fatigue leads many to disengage from international events, especially those not perceived as directly relevant (YouGov, 2024).

Social Media: Accelerators of Fragmentation

Social media plays an ambivalent role in how conflict-related information spreads. On one hand, they allow for rapid, horizontal dissemination of alerts, testimonies, and field videos. On the other, they accelerate the pace of information consumption, often sacrificing depth and accuracy. Disinformation expert Claire Wardle notes that platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, or TikTok “are not designed to help us understand the world, but to hold our attention as long as possible through emotion and polarization” (Wardle, 2022).

This algorithmic logic reinforces visibility biases. The most « spectacular » conflicts or those with familiar geopolitical narratives get more coverage. Others, like Sudan or eastern DRC, are viewed as « too complex, » « chronic, » or « geographically marginal » and struggle to break through. Lacking powerful narratives or recognizable figures, these crises disappear from the global radar.

This is not new, but social platforms intensify the implicit hierarchy of tragedies. As Dominique Cardon writes, “the architecture of digital platforms creates an emotional selection of the world, where tragedies compete for existence” (La démocratie Internet, 2010). This creates a “market of emotions,” where outrage is volatile, reversible, and often shallow. The war in Gaza, for instance, has received wide social media coverage due to widespread amateur videos and direct testimonies. Meanwhile, the war in Sudan, just as tragic, remains largely ignored.

Inequality in Representation and “Silent Tragedies”

This hierarchy of attention is not neutral, it reflects and perpetuates power dynamics. As the French think tank IRIS recently stated, “in the Western collective unconscious, African or Arab lives continue to be worth less than others” (IRIS, 2024). This media imbalance isn’t just about visibility, it directly impacts political mobilization, international aid, recognition of suffering, and even collective memory. Forgotten or sidelined conflicts inflict a double violence: first, the tangible harms suffered by affected populations; second, the silence that surrounds their suffering—the absence of symbolic, political, or media recognition.

Anthropologist Michel Agier refers to this as “humanitarian invisibilization”, a selective forgetting where certain bodies, voices, and pains are excluded from global public space.This context calls for a rethinking of how prolonged conflicts are narrated and represented. It requires dismantling Western-centric media reflexes, but also embracing slowness and depth in analysis—to escape the news cycle and rediscover meaning. As Bernard Stiegler suggested, “restoring attention is restoring the ability to think a shared world” (Stiegler, 2004).

This hierarchy of visibility does not remain without effect. It shapes the way international institutions prioritize, or neglect, certain conflicts. When attention collapses, political and humanitarian action follows. It then becomes essential to ask: why do some prolonged tragedies, despite their intensity, escape any lasting response from the international community?

International Disengagement: Causes, Biases, and Mechanisms

In the face of persistent systemic violence in regions such as Gaza, Sudan, or the Democratic Republic of Congo, a crucial question arises: why do some prolonged conflicts escape the sustained attention and action of international institutions? This disengagement is not merely circumstantial or logistical; it is rooted in geopolitical, racial, and economic dynamics that structure the international order. By analyzing the mechanisms of concealment, institutional inertia, and the consequences of prolonged inaction, it becomes possible to shed light on the blind spots of international solidarity.

Selective Geopolitics and Interest-Driven Logic

International institutions such as the United Nations, the African Union (AU), or the European Union present themselves as guarantors of global peace and security. Yet their ability to intervene remains deeply conditioned by unequal balances of power. The UN Security Council, for instance, becomes paralyzed whenever its permanent members, China, Russia, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom, fall into disagreement. António Guterres, Secretary-General of the UN, recently denounced the Council’s “strategic impotence” in ending conflicts, due to deep divisions over Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan (AP News, 2024). These deadlocks reflect an instrumentalization of international law for the sake of competing geopolitical interests.

The conflict in Sudan clearly illustrates this inertia. While more than 15,000 civilians have been killed and 9 million displaced since 2023, the UN has adopted no major binding resolution. The arms embargo, symbolically renewed by the Security Council, remains ineffective in the face of the circulation of weaponry supported by regional powers (AP News, 2024). The absence of a robust mandate reveals a tacit hierarchy: some areas, lacking clear strategic or economic interest for the great powers, are left adrift. In an article published in the Yale Journal of International Law (2024), researcher Sarah R. Berman emphasizes that “the application of international law is strongly correlated with states’ positions in the global economic hierarchy”: fragile states, outside of major alliances, receive little legal attention, while powerful states benefit from a form of structured impunity. This institutional asymmetry contributes to what some call a “geo-selectivity of justice,” where mass crimes in countries such as the DRC or Yemen trigger neither sanctions nor robust international investigations.

But beyond geopolitical and legal dynamics, another structural factor weighs heavily on international disengagement: the way certain lives, depending on their origin, are perceived as less worthy of attention or protection. This is where colonial legacies, racial biases, and unequal patterns of development intersect.

Racial and Colonial Biases

Indifference toward certain conflicts cannot be explained without taking into account the colonial legacy and the persistent racial biases within the international system. Several scholars and organizations denounce a structural inequality in the recognition of human suffering: tragedies affecting Black or Arab populations generate less media and political empathy than those involving Western countries or their close allies (IRIS, 2024). This hierarchy is evident in the disparities of media coverage between the war in Ukraine—which mobilized rapid and massive solidarity—and those in Sudan or the DRC, which have in fact been deadlier in terms of civilian casualties over time.

This logic of racial differentiation also extends to the mechanisms of humanitarian aid. A study in the Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law (2023) shows that emergency funding allocated by international institutions is heavily biased: in 2022, the funds mobilized for Syria or Ukraine exceeded by more than ten times those directed to East Africa, despite the latter facing famine exacerbated by armed conflicts. This disparity is not explained solely by humanitarian severity but also by economic and geostrategic interests. Regions deemed crucial for energy stability, trade routes, or regional alliances, such as Eastern Europe or the Middle East, concentrate attention and resources. Conversely, marginalized regions of the African continent, considered less strategic or less profitable in the short term, struggle to attract aid despite the scale of their needs. This structural inequality reveals a mode of hierarchy in which suffering is measured not only in human lives but also in geopolitical and economic value.

Consequences of Prolonged Inaction: Distrust and Secondary Trauma

Repeated inaction from international institutions severely impacts affected societies. In prolonged conflict zones, the feeling of abandonment fosters deep distrust, not only toward international authorities but also NGOs perceived as powerless or selectively present. In Sudan, many survivors accuse the UN of leaving civilians “in the hands of militias” without effective protection or evacuation (The Guardian, 2025).

In Gaza, MSF doctors report that the absence of a ceasefire and diplomatic paralysis exacerbates war’s psychological toll. “The repeated silence in the face of massacres creates secondary trauma, that of not being seen or heard,” said a Gaza-based psychologist in May 2024 (MSF, 2024). This sense of institutional invisibility erodes social cohesion and sometimes fuels radicalization. In the DRC, where armed group atrocities continue in relative international silence, this disillusionment is also strong. The narrative of “forgotten communities” is widespread, and collective memory is shaped by abandonment. Congolese researcher Jacques Bisimwa writes: “It’s not just war that destroys us, it’s knowing the world looks away” (Bisimwa, 2023).

Finally, this prolonged disengagement erodes the legitimacy of multilateralism itself. The UN’s post-1945 promise of a “rules-based international order” appears increasingly empty to populations in the Global South, who view indifference as institutionalized contempt. This fosters collective feelings of abandonment, undermines trust in institutions, and weakens social bonds.

But these wounds do not remain confined to the present. They seep into family memory, take root in silences, glances, and fears passed from generation to generation. What war destroys, it does not rebuild on its own. It leaves behind invisible scars, legacies of fear and loss that children carry without understanding. In places like Gaza, the DRC, or Sudan, wars do not end with weapons. They live on in bodies, dreams, and ways of inhabiting the world. There begins another, slower, quieter struggle, the psychic repair that must follow political devastation.

AUTHOR : Yousra Erraghioui

ILLUSTRATIONS : Alba Gutiérrez